Are You Medical OEM Material?

As the baby-boomer generation inexorably falls apart, screws, plates, rods and less invasive surgical tools are increasingly available to put "humpty" back together again. A question for many precision part makers is, "How do I get into the medical machining game?" To find out, we talked to a major OEM about its supplier selection criteria.

Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc. (EES) is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of medical devices for open and minimally invasive surgical procedures. Among the company’s prime directives for itself and its manufacturing supplier base is an understanding that the end products produced for use in the medical industry are of vital importance for the patients whose health and lives are dependent on them. EES takes this role seriously and asks its suppliers to do likewise.

To find out how the company selects suppliers to augment its manufacturing capability, I sat down with Jerry Morgan, principal engineer for research and development. He’s a former toolmaker and understands metalworking technology and shop practice.

EES traces its roots back to the 1980s when industrial fastener maker Senco partnered with suture giant Ethicon, Inc. (Somerville, New Jersey) to produce surgical stapling technology. In 1992, EES, located in Blue Ash, Ohio, a suburb near Cincinnati, was formed as a separate division to further develop new technologies for open and minimally invasive procedures.

Originally, the Blue Ash facility performed both R&D and manufacturing at its campus. “Back then, our product offering was fairly limited, and we simply used the blanking and forming suppliers that Senco had dealt with,” Jerry says. “As the product line grew, we began using larger volumes of titanium, aluminum and stainless, which required a more diverse base of suppliers. We also outgrew our manufacturing space in Cincinnati.”

Today, in addition to the myriad functions of a corporate headquarters, the campus is also home to R&D and operations, which interface with the supply chain, as well as customer training. Customers, in this case, are doctors and other medical professionals who get hands-on experience using EES products in simulated surgery training labs.

Why Mess With Medical?

The short answer to why the medical device market is attractive to manufacturers is growth. From a report prepared by Swiss machine tool builder, Tornos Technologies U.S. Corp. (Brookfield, Connecticut), the annual sales by the medical device sector has exceeded $200 billion in the past 2 years. Overall, the medical device market is expected to post a global growth rate of 6 to 8 percent per year.

Specific segments within the overall market should see even higher percentage growth. Orthopedic products used for traumatology, spinal surgery and instrumentation showed growth rates of 15 to 20 percent over the past few years. The cardiovascular field that uses extremely small, high-precision parts found in pacemakers and defibrillators shows a growth of 10 to 20 percent. Implants and devices and instruments used for intervention in the dental segment have seen a growth of 10 to 15 percent.

It’s not a huge leap to surmise that medical-device OEMs, such as EES, and their suppliers are involved in the highest and fastest rates of industrial growth worldwide. Although the main world market leaders in the implant and instrumentation sectors all have captive manufacturing facilities, the volume and variety of parts being manufactured is constantly growing. The OEMs and their design engineers require an efficient network of subcontractors, capable of supplying parts, capacity and proficiency, that offer a competitive advantage to help keep pace with global market demands.

OEM/Supplier Relations

At the end of the day, far too many metalworking shops measure their success by counting the “good” parts shipped out to customers. However, simply meeting shipping schedules, whether JIT-driven or driven by some other contractual arrangement, is only one aspect of the kind of relationship that EES is looking to perpetuate with its suppliers.

The truth is that in medical machining and other industry segments, a shop’s ability to manufacture and deliver quality parts is simply one checkmark in a given column. Medical-device OEMs like EES realize that the parts a shop makes are a result of the processes, business practices and culture behind their manufacture.

“We look at suppliers systematically,” Jerry explains. “Evaluations include the shop’s quality system. Who in the shop is empowered to stop the train if a quality issue is identified? What is the company’s business strategy? Does it have a long-range plan?

“Does the shop have one critical customer, or does it spread the business among many customers? How about training and education of the workforce? Is a program in place for ongoing skills development? Among the most critical items is cost models. Does the shop know where the costs of manufacture are in the process? Can it help educate EES designers about the cost impact of a given design and help work out a design that fits the shop’s manufacturing process? Does the company do internal R&D or simply manufacturing? How well does the shop integrate prototyping and process development into production capability? A potential supplier shop needs to know how to explain these things,” Jerry says.

A Two-Way Street

In the highly competitive world of manufacturing, enlightened OEMs realize that a fair and equitable relationship between them and their suppliers is ultimately in the best interest of the OEM.

The assessments EES performs are also tailored to the supplier. For example, a screw machine shop, fabrication shop or an injection molder is weighed differently than a multi-faceted Tier One contract manufacturer. “However, in general, we want to work with companies that have high ethical standards, a tested track record and are in business for the long haul,” Jerry explains.

EES is built on growth. Its medical device business mirrors the burgeoning global demand for its products. Obviously, supplier companies must be able to grow, too. Part of the supplier assessment process is to help determine how much “head room” a company has.

“Our growth is tied to the growth of our suppliers,” Jerry says. “In many cases, we’ve seen our suppliers grow their business exponentially. Now that kind of growth isn’t for everyone. Over time, we’ve fine-tuned the assessment process to a point where we can usually spot the kind of company that can grow with us.”

An example of the need for supplier flexibility was a product that EES introduced last summer. The launch was scheduled for August. Just before the release, the marketing people upped the production schedule by a factor of three. “Not every shop can absorb a 3× increase in production with such short notice,” Jerry says.

Experience like this example and others is why EES prefers to use a single supplier from the start of a project through production. It may only be one part out of ten but the supplier knows that one part.

“I’d rather use a single company for prototype development and process prove-out, and then go to production with them,” Jerry explains. “Then I have people helping with design who are up the learning curve as to the design intent, which plays an important role on the production floor.”

Design Meets Production

At any given time, EES has numerous teams active in development of new products or derivatives of existing products. Each team is built like a small company.

“A team is made of numerous disciplines,” Jerry says. We have design engineers, manufacturing engineers, QC engineers, marketing people and finance people who are coordinated by a team leader from R&D.”

Projects begin with an idea that is new or derivative. The idea is vetted for feasibility by a core team and presented to a board. If the plan is approved, the team can move forward with the project.

Occasionally, as the new product development moves forward, it becomes apparent that its manufacture requires a technology that is not in the current database of suppliers. Supplier management, which is in the operations side of the company, will go out and look for that technology.

“We use numerous means to connect with potential suppliers,” Jerry says. “Trade shows are a good venue. The Medical Design and Manufacturing series is good for us because it allows shops to exhibit in addition to OEMs. Machine tool trade shows are helpful to identify a particular machine capability from a builder who may then allow us to contact the customer who is using the technology. We’ll ask our existing suppliers about shops that can produce what we need. We’ll search the Internet. We’ll talk to other groups within our larger organization.”

In many cases, a project doesn’t require new technology, but it does require capacity that may be beyond our current supplier base. Growth is the driver, which translates to an expanding need for manufacturing capability.

“If our current suppliers can’t add the capacity needed, we need to add suppliers,” Jerry explains. Looking at the growth numbers and demographic projections for the markets served by EES and other medical-device OEMs, it’s a good bet suppliers that are positioned to pass the assessment will get work.

Assuming a shop has a handle on its business, another critical key is to make the business visible to the OEMs. Potential shops should participate in trade shows, put up a useful, informative Web site and network with other shops through local and national trade associations. In other words, they should market a capability to companies like EES that are going to need suppliers, maybe not today, but tomorrow.

It’s also important to understand the need for patience dealing with the medical-device industry. A product development cycle time for medical devices may be different from many industries that a potential supplier is used to in other industries.

“If we’re developing a derivative product, such as taking an existing product and making it longer, for example, cycle time may be 4 months,” Jerry adds. “A platform product—a technology that will form a family of like products—may take 3 years to bring to the market. A system that will be implantable may take 8 to 10 years for full approval.”

Getting In The Door

Jerry frequently gets calls from shops and manufacturing reps that are seeking an opportunity to do business with EES. He responds to these inquiries by asking, “What can you give me that I don’t already have? I’ve got a solid base of known suppliers that I’ve worked with for many years. Within the structure of my business, what does your shop have to offer? If I need capacity, that may be an opportunity. We’re vitally interested in cost reduction, but if a lower price is all a shop can offer, which is often the case, it’s a tough sell to convince us that tossing an existing relationship is worth a few cents a part. We don’t do business that way,” he says.

A better tact for potential suppliers that have the viability to work directly with a medical-device OEM, such as EES or as a subcontractor to one of its existing suppliers, is to make a company and its capabilities and willingness known.

However, Jerry has some thoughts for a more direct approach. “Forget about that ubiquitous equipment list that so many shops believe is revealing,” Jerry offers. “R&D designers are engineers, and engineers like to touch things. A better way to get our attention is to put an envelope together that includes a picture of your shop floor with a brief description of your business and who your customers are. Tell me about the kind of quality system you run. We’d also like to receive a sampling of parts you’ve made along with prints and specs. We have a full laboratory here and can perform detailed analysis on the parts, which can tell us a lot about a shop’s processes. Consider transferring this information to your shop’s Web site.”

As a potential supplier, it’s important to generate interest on the business side and the manufacturing side. Approaching a company like EES involves understanding its structure as well as its needs. Some supplier candidates, for example, will work through the operations/supplier management side of EES, along with the technical R&D side, even at the corporate level. A company that demonstrates a willingness to work with a development team to make the one or two parts as proof of concept, often finds itself in a front-running position when the product is ready for production. It takes patience, investment and perseverance for a supplier, but the rewards can be well worth it.

Medical—A New Frontier

Most metalworking shops are used to being beaten over the head by price. Shaving a cent here or a nickel there represents what little job security is available in many industry segments. It’s a business model that is based on commoditization of machined parts driven, in many cases, by mature or declining markets.

The sense that comes from interviewing Jerry is that model is not applicable to EES and for that matter, most other medical-device OEMs. They are interested in cost control, and they enforce it, but many of the parts these companies design and send out for manufacture require co-developed expertise between the OEM and its supplier. Competence is more a driver than price.

Moreover, medical-device manufacture is in ascendancy, and by most accounts, is poised to continue growing. Companies like EES often have policies that limit the amount of work, as a percentage of its production, that any one supplier can perform. That makes room for more potential suppliers that have a strong handle on their business and can get noticed. It seems that there is and will continue to be plenty of work in this segment for quality manufacturers.

Related Content

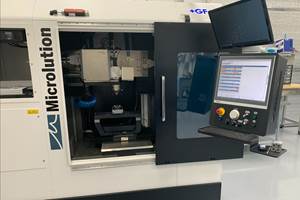

Five-Axis Machining for Small Prismatic Parts

New to the U.S. market, this compact machine could enable precision turning shops to win complex, more prismatic work in medical and other industries.

Read MoreWhere Micro-Laser Machining Is the Focus

A company that was once a consulting firm has become a successful micro-laser machine shop producing complex parts and features that most traditional CNC shops cannot machine.

Read MoreThe Control’s Role in Machining Complex Parts

This company that produces medical implants finds value in the CNC for its turn-mill equipment that helps speed setups and simplify programming when producing intricate parts complete.

Read MoreMoldmaker Finds Value in Swiss-Type Machining

This multifaceted manufacturer has added CNC sliding-headstock turning technology to complement its established mold tooling production and new injection molding capabilities as it continues to pursue complex medical work along a vertically integrated path.

Read MoreRead Next

Complex Angular Dental Implants...on Multi-Axis Automatic

Just like a car or a machine, the human body benefits from the technological progress of small parts turning equipment. Precision and stringent requirements for safety and stability are essential in the medical industry. In fact, the demands made on surgical screws (bone screws, maxillary-facial screws, implants and so on) and bio-implants can be much greater for the human body than for many industrial and commercial product applications.

Read MoreBoning Up On Thread Whirling's Advantages

Thread whirling attachments installed on this bone screw maker's Swiss screw machines prove to be just the right prescription for the company's mix of screw sizes and run quantities.

Read MoreA Tooling Workshop Worth a Visit

Marubeni Citizen-Cincom’s tooling and accessory workshop offers a chance to learn more about ancillary devices that can boost machining efficiency and capability.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)