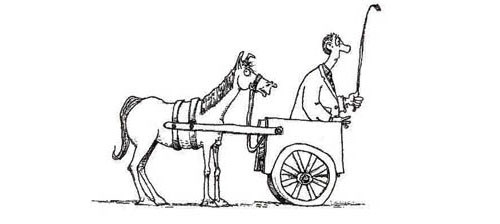

You need skills, not just high pay, to properly hitch the cart to the horse.

The New York Times’ article “

Skills Don't Pay the Bills,” gets it wrong on the skills gap, confusing cause and effect, ignoring facts and making a false analogy.

It made a couple of erroneous points:

1. Supply and demand dictate that wages should rise if there is a shortage of machinists;

2. Wages for McDonald’s managers are better than those for skilled machinists;

3. Demand for skills isn’t real.

In this post, we’ll deal with the supply and demand wages issue.

Supply and demand dictates that wages should rise if there is a shortage of machinists.

In the New York Times piece, economist Mark Price argues that “It’s basic economics … If there’s a skill shortage, there has to be a rise in wages.”

If only economics were so basic, Mark. Actually, supply and demand is the wrong issue; the issue is the elasticity of labor supply to an occupation.

In “basic economics” terms, this means where jobs require specific skills and lengthy periods of training, the labor supply will be inelastic. Inelastic means it is not possible to expand that specific labor force in the short term. “Raising the wages won’t just create them out of thin air …”

The NY Times and economist Price have confused cause and effect.

Higher wages are a consequence of having skills that add value by increasing the value and or quality of the employee’s work. Raising wages does not of itself add any tangible benefit or skill to the employee’s work product. It does, however, raise cost. Why the wages “don’t have to rise” is because, unlike the inelastic supply for skilled labor in an occupation, the supply for manufacturing work is elastic.

China and other low wage economies around the world provide low cost—often government subsidized—alternatives to U.S. manufacturing that becomes more expensive, but not more productive, if the wages just increased because Price thinks they should.

Precision machining is an occupation with inelastic labor supply. It requires specialized skills, ability to do math, and training and experience to safely perform the work to zero defects (Zero PPM) standards. The anti-lock brake, airbag and aircraft parts our machinists make need to work.

Related Content

-

Instilling confidence throughout a shop floor can do wonders for company morale while increasing productivity.

-

Roles of Women in Manufacturing Series: A precision machining career starts with skills. Virginia and Laiken share their journey and how they help prepare the next generation.

-

There are nuances to training a person to effectively operate a Swiss-type lathe. A shop I visited a while back offers some suggestions.