Knowing how to read disinfectant labels and accurately interpreting their meanings is crucial in the fight against transmitting the pathogens. (Photo image courtesy of Getty images.)

Protecting employees, customers and products from harmful contaminants is a priority for all machine shops. For example, using surface disinfectants continually is vital to prevent the spread of bacteria and viruses, most recently SARS-CoV-2 (the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 disease), in a shop environment. But unless the proper disinfectants are being used and implemented correctly, the process of disinfecting will be ineffective. Knowing how to read disinfectant labels and accurately interpreting their meanings is crucial in the fight against transmitting the pathogens.

To clarify the proper use of these disinfectants, Yangsheng Zhang, Ph.D., technical director at BHC Inc., shares his insights about what to learn from Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) labels, including their efficacy claims and how to interpret them for use against COVID-19. He also shares disinfection strategies and application methods, as well as his thoughts on post-pandemic disinfection.

The Significance of EPA Labels

Label reading is not a strong point for some people. However, it is a critical habit to have when handling chemicals. Surface disinfectants, specifically, contain important information on their labels dictated by the EPA. The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenitcide Act (FIFRA) requires that all disinfectants must go through an EPA registration and approval process with the Antimicrobial Division, Office of Pesticide Program before the products can be manufactured or sold in United States. This registration results in an EPA registration number that appears on each product label. Products must also be registered at the state level.

“Approval requires the disinfectant manufacturer to use data to demonstrate efficacy against the microorganisms that they are claiming to kill, as well as provide safety data to make sure the solution is safe for the environment and humans,” Zhang explains. “Non-EPA-approved products are prohibited to make any explicit or implicit disinfecting claims.”

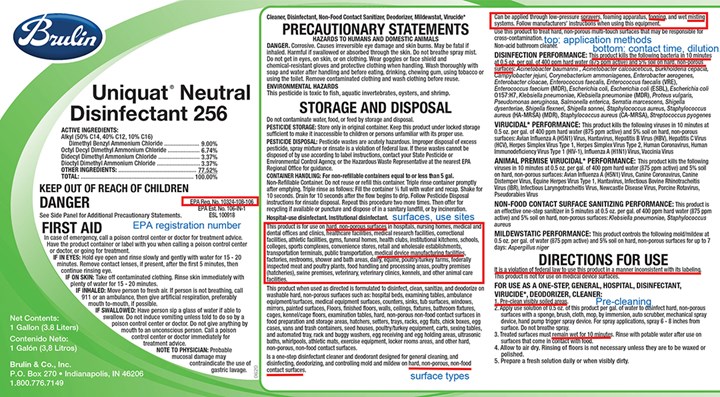

The EPA label’s purpose is to provide confines that hold the user responsible for staying within them for effective disinfecting and safety. The more critical information is in the red highlighted areas. (Photo courtesy of BHC Inc.)

Beyond the formalities of gaining EPA registration, the label’s purpose is to provide confines that hold the user responsible for staying within them for effective disinfecting and safety. And, according to Zhang, it is a violation of federal law to use EPA-registered products in a matter inconsistent with its label.

He compares the importance of using these disinfectants correctly (as stated on their labels) with interpreting parts cleaning solvent labels properly. “We can draw parallels for the precision cleaning professionals when they find a (cleaning agent) product that is conformed to OEM approvals and industrial specifications,” Zhang explains. “They are supposed to follow those specification approvals and procedures, and not migrate outside of them.”

EPA labels also include an active ingredient list, concentration of the ingredient, efficacy claims, dilution ratio, contact times, surface types, use areas, application methods and directions for use.

Efficacy Claims and COVID-19

First, for disinfectants to be effective on a surface, precleaning is necessary. “Soils act as a protective barrier to pathogens and prevent the disinfecting agent from contacting the bacteria and/or virus particles to destruct the proteins,” Zhang says. He adds that, although new EPA efficacy protocols require the use of 400 ppm hard water and 5% serum to represent the light soils during testing, applying disinfectant on heavily soiled surfaces without precleaning them is a waste of time. “Cleaning is the only effective way to remove pathogens attached to or embedded in the surface soil,” he says. “Therefore, disinfecting after cleaning is the only way to ensure that the surface is fully decontaminated.”

“Continuing to decontaminate a workplace even after the pandemic is over might be the best routine to keep other viruses and bacteria at bay.”

Second, pairing efficacy claims to pathogens that shop management is concerned about is critical when choosing an effective disinfectant for a particular environment. This is because different microorganisms listed on the label can have different dilution and contact time. Normally, one would look on the label for the dilution and contact time for the pathogen he/she wants to kill. However, unlike established pathogens (such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV), novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is not yet listed on product labels.

To address this issue, the EPA has established an Emerging Viral Pathogen Program that provides clear guidelines as well as authorization for users to select appropriate disinfectant against an emerging viral pathogen (such as the SARA-CoV-2 virus) based on existing label claims. This program is triggered only if the CDC confirms there is an outbreak and it inactivates 100 days after the outbreak has ended. “The principle behind the authorization is based on scientific evidence that the susceptibility of pathogens to chemical disinfection correlates to the virus structure,” Zhang says.

He continues by explaining enveloped, large (50-nm) non-enveloped and small (< 50-nm) non-enveloped viruses and how this model helps determine which disinfectants to use against new outbreaks. The SARS-CoV-2 virus is an enveloped virus, which is the easiest of the three virus classes to kill. Knowing this, the EPA’s Emerging Viral Pathogen Program allows products that are effective against small non-enveloped viruses to claim efficacy against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. “Because small non-enveloped viruses are harder to kill, if a product is effective against that, then the product is expected to be effective against a virus that is easier to kill,” Zhang explains.

The norovirus is a common, small non-enveloped virus that most disinfectant manufacturers use as the basis to make emerging viral pathogen claims against SARS-CoV-2 virus. “Such claims allow you to use such product to fight COVID-19 when following the use instruction for norovirus,” Zhang says.

A list of based registration disinfectants approved to make SARS-CoV-2 claims under the emerging viral program (EVP) can be found in List N on the EPA’s website.

Disinfection Strategies

It’s critical to use a disinfectant that is formulated for hard, nonporous, inanimate surfaces. The product should also explicitly list “manufacturing facility” on the label as one of the use sites for the disinfectant to be applied. (Photo courtesy of Getty Images.)

Understanding that a disinfectant is formulated for specific surfaces and learning how to find this information on the label are other essential steps for proper prevention of COVID-19. All EPA-approved labels clearly specify the surface types on which the disinfectant should only be applied. Zhang recommends finding a disinfectant that is for hard, nonporous, inanimate surfaces. These surfaces include benches, tables, desks, doors, handles, machine controls and push carts. The product should also explicitly list “manufacturing facility” on the label as one of the use sites for the disinfectant to be applied.

Knowing where to apply disinfectant then leads to the next step of how often to apply it. Zhang points to using a risk mitigation strategy to determine targets for frequent (or infrequent) disinfection. “Risk is a combination of hazard and exposure,” he explains. “A high hazard with no exposure leads to low risk, and a low hazard with high exposure can actually mean higher risk.”

Based on that concept, Zhang advises shops to consider initiating a risk assessment of all surfaces, which entails identifying touch points throughout the facility and then categorizing those touch points as high or low touch points. “The high touch points will be your primary targets for frequent disinfection because they are the surfaces with more chances to transmit the pathogen,” he says. These high touch point objects can be anything from machine controls and door handles to writing pens for a white board. These should always be pre-cleaned. “I won’t necessarily recommend manufacturers spray disinfectant over floors and walls,” he adds. “They can do that now and then, but they aren’t high touch points.”

Application Methods

Although spray is a common method for applying disinfectant, there are other methods that are approved by the EPA. These methods are listed on an EPA label. (Photo courtesy of Getty Images.)

Once management has chosen the appropriate disinfectant for the shop environment and is ready to apply it to the appropriate shop surfaces, using the application methods listed on the EPA label is essential. Although spray is the common method, there are other methods that are approved. “For example, if you want to use a fogger to disinfect a small space, you must use a product that specifically lists ‘fogger’ as one of the application methods on the label,” Zhang explains.

Continuing Disinfection Post-Pandemic

Although it has become commonplace to disinfect surfaces regularly since the COVID-19 outbreak, continuing to decontaminate a workplace even after the pandemic is over might be the best routine to keep other viruses and bacteria at bay.

“The COVID-19 event really opens up a new perspective on how we deal with these hidden enemies, so to speak,” Zhang says. “Thinking back to flu viruses we have dealt with, we are probably underprotecting ourselves. Luckily, the flu is not as fatal as coronavirus, but it prevails and is everywhere.”

Keeping a routine and correct practice of disinfection will help operations have a healthy workforce and reduce the amount of sick days employees take, he concludes.

For the EPA’s list of disinfectants for use against COVID-19, visit gbm.media/coviddisin.

Related Content

When a CNC Turn-Mill Doesn’t Turn

A shop in Big Sky Country uses a B-axis multitasking machine to produce complex, prismatic medical parts that require no turning complete from barstock.

Read MoreWhy Are We Writing About a Shop Making Custom Baseball Bats?

I recently learned about a 153-year-old manufacturer that has produced billions upon billions of precision, metal pins which started another business making one-off wooden baseball bats. (Like I asked it to do for me and you’ll see at this year’s Precision Machining Technology Show). Here I explain why it’s worth the time to read that article.

Read MorePursuit of Parts Collector Spearheads New Enterprise

While searching for a small parts accumulator for Swiss-type lathes, this machine shop CEO not only found what he was looking for but also discovered how to become a distributor for the unique product.

Read More6 Tips for Training on a Swiss-Type Lathe

There are nuances to training a person to effectively operate a Swiss-type lathe. A shop I visited a while back offers some suggestions.

Read MoreRead Next

Our Precision Machining Industry Responds

This moment-in-time article describes the challenges multiple precision machine shops faced — and met — to support customers’ and employees’ needs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Read More5 Aspects of PMTS I Appreciate

The three-day edition of the 2025 Precision Machining Technology Show kicks off at the start of April. I’ll be there, and here are some reasons why.

Read MoreEmerging Leaders Nominations Now Open

Here’s your chance to highlight a young person in your manufacturing business who is on the path to be a future leader moving your company forward.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)