No one in management at Accurate Manufactured Products Group (AMPG) has a manufacturing background. For the most part, they don’t know how to run machines. But rather than see this as a weakness, the team views it as a starting ground for experimentation, working with a skilled team of machinists to succeed even when making choices contrary to conventional manufacturing wisdom.

AMPG’s Star Swiss machines fill up multiple rooms at its facility. Rather than sorting them by number, the team has nicknamed each machine after famous television and film characters. Image courtesy of AMPG.

Niches and Experiments

Matt Goldberg, president of AMPG, founded the company in 1987 as a New York-based distributor of hard-to-find parts. By 2001, some of these parts had grown hard enough to find that he bought manufacturing equipment to make them in-house. He moved the business to Indianapolis and began putting together a team, including his son Alex Goldberg (managing partner and vice president of sales), his son-in-law Nelson Cruz (vice president of manufacturing) and Linda Thompson (vice president of finance and operations). None of them had much experience with manufacturing — Cruz even came straight into his management position from a marketing job — but with Matt Goldberg’s advice to trust in the machinists and not manage too closely, they have found great success. Matt Goldberg, Alex Goldberg and Nelson Cruz all say that this is not counterintuitive, but stems directly from their lack of experience.

“We don’t know what can and can’t be done on these machines, or in the shop, or any shop in general,” Cruz explains. “So we always challenge it. Someone with more experience knows what’s ‘possible,’ and maybe doesn’t take that risk.”

This includes selecting AMPG’s niche: specialty fasteners and components, made with Star Swiss machines. While the parts are more expensive than the average fastener, the process is still what Geoff Dugan, process engineer, describes as “delivering pizzas with a Ferrari.”

Like its tooling, each type of stock at AMPG corresponds to a barcode. This helps AMPG’s team track material usage and restock only when necessary, which is useful, given the wide variety of materials and sizes the shop uses. Image courtesy of AMPG.

Premium Price, Premium Process

One reason AMPG can command higher prices is speed: it turns around most parts within a week. The shop works heavily with distributors, but its ultimate clients typically need small quantities or prefer just-in-time parts. These clients work in a vast array of industries, from robotics to architecture to spaceflight, requiring lot sizes around 300 pieces. AMPG fulfills about 400 of these orders a day, at tolerances down to 0.0005 inch.

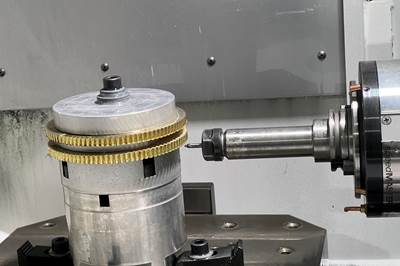

To do so, it makes use of a fleet of 60 Star CNC Swiss machines. These machines handle fasteners smaller than a 1.5-inch diameter, while six DN Solutions lathes and two larger Hyundai lathes handle larger parts. The shop also uses one vertical and one horizontal Hyundai mill for parts that require additional operations, as well as several manual machines.

This is an expensive group of machines; Matt Goldberg says each Star Swiss machine can cost around $600,000, while the parts may sell for around $2. This situation may not immediately appear viable, but he says that the high-end machines ensure his team doesn’t fight with machinery and tolerances on the shop floor. Instead, he says they produce high-quality parts quickly, fulfilling the shop’s promise of “beautiful parts, right now.”

Still, this is a hefty number of machines, and AMPG runs two shifts with only 12 Swiss machinists; four people on secondary operations such as thread rolling and manual work; and six people on support for cleaning oil, washing parts, bringing material, setting out tools and the other tasks that keep the shop floor running. It does so by eliminating paper processes and implementing digital aids — namely, adding machine monitoring software, digitizing QC data, and designing a seamless information flow between the machines and the engineering department.

“It’s like we’re delivering pizzas with a Ferrari.”

AMPG uses SMOOSS-I, an in-house machine monitoring software built into its Swiss machines. According to Star’s representatives, AMPG might be the only shop in North America using the software. SMOOSS-I enables machinists to see the status of jobs on machines in real time, a functionality the shop uses for scheduling, staffing and customer status reports. It is also starting to use this software to monitor tool life on jobs with hard materials to ensure they can run lights-out. The goal is to match the performance of the shop’s 316 Stainless jobs, which are already optimized for full lights-out work.

Innovating with Automation and More

These optimizations are just the latest steps AMPG has taken on its automation journey. The shop uses multiple automation methods across its machines, which together enable it to efficiently produce around 50,000 different part numbers.

For the Star machines, AMPG makes use of bar feeders and complex macros. Because its part families tend to differ only in length, the shop has found it simple to program subroutines where the only variables are the length of the part and the number of parts. These machines can then run unattended for the length of the full routine, which currently lasts up to five subroutines — though the shop is hoping to expand this out to 25 subroutines (five groups of five). This automation could send the shop from its current 16- or 17-hour uptime to full 24-hour production.

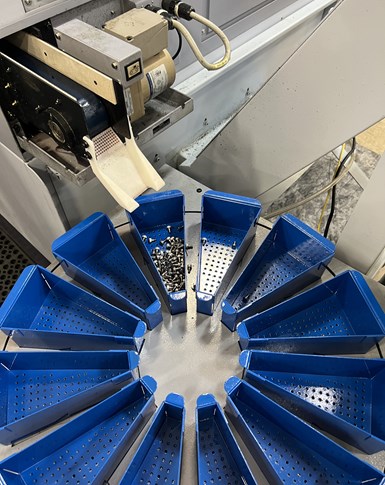

Now that an M-code controls both the machine and the part collection table, either can be reset without mixing up parts from different subroutines.

There are limitations to this design, but AMPG has been working to address them as they come. For example, initial runs of the five-subroutine programs would produce parts in order, but deposit them in a single tray where they would be jumbled together. The shop introduced a table to keep the parts separate, but it was programmed separately from the machine, so resetting one or the other due to an error threw the system out of sync. Now, both are controlled via a single M-code in the program so they work in sync. The shop would also like to automate its Swiss machines to work on different part families in the same program, but it is still developing methods to compensate for its limited tooling positions on each machine.

Another potential issue with this automation method? The size of the resulting parts. Programming for length is simple, but dealing with different diameters and thicknesses requires another solution: machining stock of the largest common size. This has its limits: reducing ¾-inch bar stock to ¼-inch bar stock is just too inefficient, for instance. But using ¾-inch barstock for a combination of jobs requiring ¾-inch and ⅝-inch barstock works well for the shop. As with using expensive Swiss machines for fasteners, this may not make sense at first blush. But while using larger stock is more expensive and can slow cycle times, the gains on setup time make up the difference.

AMPG does not produce customer-facing parts with its 3D printers, but the time-saving devices and repair parts the shop prints have streamlined processes and ensured it can continue producing high-quality parts quickly.

AMPG also makes regular use of polymer 3D printers. The shop originally bought a printer for a part where they couldn’t waste the material, but it gathered dust until the COVID-19 pandemic. In the pandemic’s early days, they used the printer to help produce face masks. One of the shop’s engineers soon took an interest in the machine and began experimenting. This quickly turned into in-house development of support and repair parts, and an attitude of, “If we can’t get it right away, can we 3D print it?” according to Cruz. Whether holders for tools, parts for an in-house oxidization station, repairs for a broken fan or, yes, grippers for a robot, the printers are in constant use for facilitating smoother work processes. The shop now owns four printers and has an in-house waiting list for 3D printed time-savers and gadgets.

To meet tight tolerances on all its equipment, AMPG has expanded the importance of its testing and quality control department. Every part number that comes off a machine gets its first and last parts tested, as well as representative parts for longer runs. A wide array of equipment is already set up in the shop’s quality control center, but AMPG also plans to expand this with a climate-controlled A2LA-certified quality control lab.

Collaboration and Community

Giving space to AMPG’s small staff to manage all these machines would be impossible without a culture of trust, responsibility and collaboration. AMPG’s leadership says they try to lead by example, listening to shopfloor employees’ ideas and deferring to them when possible. Even machine monitoring data is meant for improving machines rather than for examining any one machinist’s productivity, according to Cruz. As a result, the shop’s leadership team says an openness to collaboration has rubbed off on shopfloor employees without an official, top-down mandate to work together.

This collaborative model differs from most traditional machine shop processes, and the shop has let go experienced employees who haven’t fit into this culture. AMPG has had a lot of success hiring through word of mouth from its current employees, and turning to people with no experience in the industry.

More important than experience has been hiring for attitude and personality, and management has developed its own character requirements and personality tests to try screening for this. Most important, though, is the actual interview, where all the leads for the job candidate’s department interview the applicant, rather than the heads of the company. As Cruz reasons, the department heads need to collaborate with the new employee, not him. Only when the team reaches unanimous agreement does management proceed with hiring.

For automating non-Swiss machines, AMPG has taken its first steps with cobots. One cobot is stationary, assigned to one of the DN lathes, while the other is taken to different places around the shop as the need arises. Image courtesy of AMPG.

This strategy requires that employees all have the company’s best interests at heart when conducting interviews. In addition to the shop culture, Alex Goldberg credits the shop’s monthly profit-sharing program with helping instill this desire for the company’s best interests. Every employee is invested in having disciplined coworkers who are easy to work with, as it improves how much they take home with the program.

Once candidates are hired, they shadow experienced employees and follow along using a textbook that shows entire setups step-by-step, with room for notes. The shop doesn’t have a strict timetable for when new employees must work independently, only requiring that they are enthusiastic about improving. As time goes on, they learn and take on more complicated tasks. Collaboration on the shopfloor means this learning never really ends. The machinists of AMPG continue to train each other and help one another grow.

Beyond the workplace, AMPG also takes some unorthodox interests in the local community. While sponsoring the robotics team that one of its engineers coaches may not be all that surprising, the shop is also quick to donate parts to art installations and to the schools that employees’ children attend. Multiple people in management also have connections to Indianapolis’ music scene, and the shop recently sponsored an international violin competition held in the city.

It is these unorthodoxies which make AMPG stand out and give it its strength. Decisions and investments that seem counterintuitive at first have become central to the shop’s processes and success. A culture that diverges from traditional manufacturing (and indeed, general business) truisms has led to higher morale and productivity. Alex Goldberg is quick to describe AMPG as more of a technology company than a manufacturing shop, but whatever he calls it, it is successful.

Sometimes delivering pizzas in Ferraris is the right call.

Related Content

Piezoelectric Sensor Technology: Moving Toward more Efficient Machine Monitoring

A new system that uses simple and compact force or strain sensors, which can be integrated inside toolholders or mounted on surfaces such as spindle housings, can facilitate CNC machine monitoring.

Read MoreThe Value of RFID Machine Operator Authentication

Can secure shopfloor employee authentication via radio frequency identification enable shops to optimize their data-driven manufacturing efforts?

Read MoreCNC Machine Shop Employment Positions to Consider Beyond Machine Operators

Many machine shops have open machine operator positions to fill. But does it make sense for shops to also seek automation engineers, IT managers and assembly personnel?

Read MorePrecision Machining Technology Review January 2023: Automation & Robots

Production Machining’s January 2023 showcase includes some of the latest technology from ABB, Mini-Mover Conveyors, FANUC, OnRobot, ATI Industrial Automation and FOBA Laser Marking+Engraving.

Read MoreRead Next

The Right (Machine) Tool for the Right Job

This high-production shop uses both mechanical and CNC Swiss machines to make parts, but which machine is right for which job?

Read MoreFour-Axis Horizontal Machining Doubles Shop’s Productivity

Horizontal four-axis machining enabled McKenzie CNC to cut operations and cycle times for its high-mix, high-repeat work — more than doubling its throughput.

Read MoreESOP Solidifies Culture of Continuous Improvement

Astro Machine Works’ ESOP rewards all employees when the shop does well, inspiring many toward continuous improvement as Astro expands its capabilities.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)