No-Burr Threading Helps Shop Compete

With the switch from a ground top-notch tool to a pressed Ingersoll threading form tool on one high-volume job, Warren Screw Machine eliminated 2 minutes of hand deburring per part. Not incidentally, the company also lopped 20 seconds per part off the threading cycle.

If you believe hand deburring is an unavoidable evil in external thread cutting, recent experience at Warren Screw Machine (WSM) in Niles, Ohio, should come as good news. With the switch from a ground top-notch tool to a pressed Ingersoll threading form tool on one high-volume job, the company eliminated 2 minutes of hand deburring per part. Not incidentally, they also lopped 20 seconds per part off the threading cycle.

WSM runs 16-hour days, 5 days a week, producing machined and ground parts mainly for the aerospace, hydraulics and automotive industries. Part volumes range from 100 to 150,000 pieces per year. One part family – several sizes of threaded plug – is a 250,000-pieces-per-year job and the biggest piece of business in the shop.

“On that job alone, we project a $190,000 gain from all sources with this drop-in retooling,” says John Condoleon, WSM president. “The gain includes labor and tooling savings as well as freed-up machine capacity stemming from reduced threading cycle times.”

Lean Manufacturing: The Trigger

The company focused on the deburring bottleneck as part of its ongoing lean manufacturing campaign, which at the time was attacking handwork on a plant-wide basis. “That formal process forced us to study, and solve, a problem we had often pecked at in the past but never got rid of entirely,” says Mr. Condoleon. “We would try a new threading tool, would see that it didn’t completely eliminate the handwork, and let it go at that. This time, we resolved to not quit until we literally reached zero manual deburring.”

WSM produces the plugs with Ledloy 12L14 free-cutting steel on a Hitachi Hi Cell bar-fed CNC turning center and Okuma bar-fed CNC lathes. These plugs are the highest-volume parts that the company produces, with an annual volume of 150,000. They are 1 ½ inches in size, produced in 5,000-piece lots. The complete operations sheet includes turning, center drilling, machining the standard Class 2 UN threads, rerunning the turning tool over first and last thread, and cutoff, followed by 2 minutes of hand deburring. “In fact, manual deburring was taking longer than all the machining,” says Craig Rossi, lean manufacturing engineer.

The previous threading tool was a ground 60-degree flat-topped carbide single-point tool (two edges per tool), also called a “top-notch tool.” Running at 432 sfm with water-based cutting fluid, the threading operation took 16 passes and 45 seconds to complete. Edge life averaged only 50 pieces because the sharp ground edges broke down so quickly. And then, inevitably, came the tedious hand deburring that added 25 cents of cost to every part. The same problem arose for every piece.

“We regard every job we have as one we could lose offshore unless we continuously grow more efficient and competitive,” says Mr. Condoleon. “Right now, getting rid of low-end manual work is our quickest ticket to improved efficiency.”

To eradicate the hand deburring, the WSM lean manufacturing team asked its Jergens distributor rep, Don Gilanyi, for ideas. Mr. Gilanyi, in turn, brought in Ingersoll’s Jeff Hogya to demonstrate the company’s new pressed-carbide form threading tool. “Frankly, we were surprised to hear Ingersoll made threading tools,” says Bill Southern, WSM tooling engineer. “We always thought of them mainly as a milling tool house. Our guys attended Ingersoll seminars and found them valuable, but we focused so much on milling, the thread-burr issue never even arose.”

Testing The New Tool

Back on the WSM shop floor, Mr. Rossi and Mr. Southern chose the 1 ½-inch plug for the test part. As the highest-volume part in the shop, it stood to produce the biggest savings if the new tool worked. Initially, Mr. Hogya set up the new tool to run at 500 sfm using the same cutting fluid and to take the same 16 passes as before.

On the first run, there were absolutely zero burrs—even after 500 pieces. “We knew we were onto something,” Mr. Rossi says. Adding to the new tools was its lower unit cost and the additional edge, thereby reducing the cost per edge and tooling inventory requirements.

Kicking It Up A Notch

After Ingersoll and Jergens left the picture, Mr. Southern continued to tweak the settings. “Ingersoll trainers always stressed pushing the tool beyond initial recommended settings at their milling seminars, so we decided to take their word.”

The result: The threading operation now runs at 600 sfm and needs only 13 passes, cutting 20 seconds from the original 45-second threading cycle. Still, the parts are 100-percent burr-free, and there’s no loss of edge life. The savings for retooling this single operation totaled more than 70 cents per part or a projected net annual savings of $190,000 for the whole family of plugs.

The breakdown: $74,000 in freed-up capacity because of shorter cycle times, $67,000 in labor savings by eliminating manual deburring and $47,000 in tooling cost savings because of the 10 to 1 gain in edge life, the third edge and the lower cost of pressed versus ground inserts.

Stronger Pressed Insert

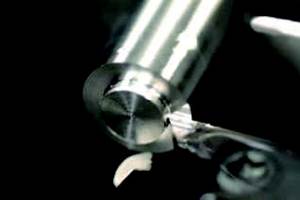

Several key physical differences between the old tool and new Ingersoll 16ERM 12 UN TT9030 account for the improvements. According to Mr. Hogya, “First, as a pressed form tool with a full nose and crest radius, the insert itself is fundamentally stronger than a ground single-point tool. Second, the pressed insert has a slight radius on the cutting edge and chip-breaking geometry on the top face. It’s not ground with a flat top and sharp edge. The small edge radius eliminates the weak sharp edge that breaks down so easily on ground inserts and causes the burrs. The chip-breaking top face clears out the chips, and the heat, so the tool runs cooler. Pressing the insert to final shape also eliminates the expense of grinding carbide, which is always considerable. Finally, each insert provides three, not two, cutting edges as before, so it’s win-win-win-win situation.”

Although WSM is pursuing its lean manufacturing program for all manual jobs, this thread retooling has been the biggest winner so far. The company started up the new process in February 2007 and has run it on about 20 percent of the plug family. “Results have been uniformly better on all sizes, so I see no reason why we shouldn’t see that full $190,000 annual gain by next February,” concludes Mr. Condoleon.

Related Content

Repeatability and Rigidity Are Key for Quick-Change Swiss Tooling

A rotary wedge clamping system is said to enable this two-piece, modular tooling system for Swiss-types to offer the performance of a solid tool.

Read MoreThe Value of Tool Monitoring on Rotary Transfer Machines

By using a tool monitoring system, shops can save costs associated with machine maintenance and downtime for tool changes while increasing cutting performance.

Read MoreTool Path Improves Chip Management for Swiss-Type Lathes

This simple change to a Swiss-type turning machine’s tool path can dramatically improve its ability to manage chips.

Read MoreShop Sets its Sights on Precise Tool Alignment

A Wisconsin shop has found that visual tool alignment technology has improved tool life and surface finishes for its Swiss-type lathes while increasing throughput as well.

Read MoreRead Next

Profile/Sharpen Multiple Form Tool Inserts Quickly

If you use carbide insert-type form tools on your screw machines and/or lathes, here’s a simple, relatively low cost way to profile and resharpen the inserts in multiples, getting the job done in a fraction of the time it would take to process them individually.

Read MoreLaser Simplifies Form Tool Chip Control

The creation of a 'bird nest' is a problem for any turning operation. These uncontrolled wads of chips tend to wreck havoc on tooling, equipment and continuous operations.

Read MoreDo You Have Single Points of Failure?

Plans need to be in place before a catastrophic event occurs.

Read More

.jpg;width=860)

.png;maxWidth=300;quality=90)

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)

.png;maxWidth=970;quality=90)